Capture and Release Research Report

by Chris Campbell - all rights reserved. No reuse without permission of the author.

INTRODUCTION

Habitat Harmony, Inc. (“Habitat”) was formed in the year 2000 with the goals of protecting wildlife and wildlife habitat in northern Arizona as well as educating the public on wildlife issues. To that end we have worked in cooperation with the Arizona Department of Game and Fish (“Game and Fish”) on several projects, relocating Gunnison’s prairie dogs. In the summer of 2003, as part of our relocation project at the Flagstaff Mall expansion site, we moved prairie dogs to the Raymond Wildlife Area, using augured holes for the first time. Due to the scarcity of abandoned prairie dog colonies that are approved for Gunnison’s prairie dog relocation, Game and Fish requested that Habitat research the technique of auguring.

During the research for this report, it became apparent that most groups that are active in relocation work do not use auguring alone as a release technique. For this reason, the research was expanded to include other release techniques that involve moving prairie dogs to areas other than abandoned colonies, as well as capture techniques. The following topics may be as useful to future relocation projects as auguring, and are included in this research report:

Capture Techniques

a. Burrow sudsing

Release Techniques

a. Auguring holes

b. Trenching with wooden nesting boxes

c. Trenching with cardboard nesting tubes

d. Visual barriers

We gratefully acknowledge that this research has been funded in part by a grant from the Flagstaff Community Foundation.

CAPTURE TECHNIQUES

The capture techniques most frequently used by experienced relocators other than live trapping are flushing and sudsing. Flushing involves using a water truck fitted with a hose to force water into the burrow. As the water enters the burrow, the prairie dogs will emerge. They are then caught, dried and put into kennels that have hay in them for transport. Flushing is no longer a popular method of capture because it often drowns some of the prairie dogs as well as other inhabitants of the prairie dog burrows.

Burrow sudsing is considered a reliable method similar to flushing, and is used by Prairie Dog Specialists, The Wild Places, Prairie Dog Action, Enviro-Zone, the City of Boulder Department of Open Space and Mountain Parks, Prairie Dog Management Consulting, Prairie Dog Coalition and Wildlife Property Management. Most relocators use sudsing in addition to live trapping. One of the relocators, Prairie Dog Specialists, has been using only burrow sudsing as a capture method for 5 years.

Burrow Sudsing / Technique. A water tank with a pump that has a valve for a water hose, fitted with a jet-spray nozzle is required. The jet-spray nozzle is used to create the suds after mild dish soap is added to the water. The nozzle is aimed at the side of the tunnel so that the stream does not hinder their movement to the surface. Because of the jet-spray nozzle, the soapsuds is mostly air, so prairie dogs and other animals are not drowned. The mild dishwashing liquid is mixed at a ratio of 3 quarts per 100 gallons of water.

As the dogs emerge from their burrows, they are caught by hand. They are then dried off with towels and saline solution is used to wash any mud and dirt from their eyes. If necessary, a bulb syringe is used to help clear the prairie dogs’ airways.

When dry, the dogs are dusted with flea powder and placed into large dog kennels filled with dry grass hay. The kennels are labeled according to family groups and placed in the transport vehicle. Each kennel is covered on three sides with a tarp to protect the prairie dogs from the sun and heat. The bottom of the vehicle is covered with a tarp to help insulate against the vehicle’s hot spots and to keep the vehicle clean.

For a brief description of the sudsing technique endorsed by the City of Boulder, Colorado, see Appendix 1. Appendix 1 also contains an article on relocation utilizing the sudsing technique by the group Prairie Dog Specialists, entitled, “Prairie Dog Lover’s Burrow.” See Appendix 2 for an article about Prairie Ecosystems Associates, a New Mexico group utilizing the sudsing technique.

Burrow Sudsing / Strengths and Weaknesses. Because the soapsuds irritate the prairie dogs’ eyes, most often all the dogs in the burrow come out and are captured. With live trapping, some of the prairie dogs, especially the younger pups, will not be captured. It is believed that relocating an entire coterie has a strong relationship to the success of the relocation. Prairie Dog Action relocators report an average 90% survival rate using sudsing coupled with trenching.

Another advantage to sudsing is that traps and bait are not a requirement, which cuts down on costs. While trapping can take two or three weeks, sudsing can usually be completed in one day. Additionally, marking or tagging the prairie dogs for future monitoring purposes is easily accomplished in conjunction with sudsing.

One weakness is that a water tank with a pump that has a valve for a water hose (which is fitted with a jet spray nozzle) is needed. Additionally, a trailer to put the water tank on must be rented. Another drawback is that fewer volunteers can be utilized due to the fact that the method involves actually handling the animals. Only Habitat board members with a wildlife handler’s license could participate in this phase of a relocation if sudsing is used.

RELEASE TECHNIQUES

Auguring Holes / Techniques. A Bobcat and a 6-inch drill bit with an extension are used to drill holes. The holes are drilled about three feet deep at a 45-degree angle. It is then best to remove all the dirt in the hole with gloved hands until the hole is clear. It is also beneficial to leave food after release so that the prairie dogs will have more time to devote to digging and finishing their new home, instead of foraging for food. It is also important to augur when the weather is dry because rain can quickly damage the augured holes or even collapse them.

Auguring Holes / Strengths and Weaknesses. This research was originally directed to auguring holes because auguring can provide alternative release sites and make relocation less dependant upon scarce abandoned colonies. This alternative would allow potentially many more release sites in northern Arizona. However, research indicates only moderate success with this method.

Augured holes do not allow adequate protection against predation while the prairie dogs finish digging their burrow system. Additionally, rain can quickly damage or destroy the holes before or immediately after the release. More experienced relocators such as Prairie Dog Specialists, The Wild Places, Prairie Dog Action, Enviro-Zone, the City of Boulder Open Space and Mountain Parks, Prairie Dog Management Consulting, Prairie Dog Coalition and Wildlife Property Management, all in Colorado, prefer to use trenches with nesting boxes.

Prairie Dog Action relocator Deb Jones has been relocating prairie dogs in Colorado for 5 years. Her experience is that auguring is not successful primarily because the dogs do not stay in the augured holes. Augured holes do not provide an immediate nesting place. Prairie dogs placed in this situation tend to fight over the best area for nesting. Only when time constraints and costs are a concern do the Colorado relocators use auguring.

Since inadequate protection from predation is a major drawback to the success of relocations involving auguring, adding an outer protective barrier or fence to an augured site might be the least expensive way to make it more plausible.

Trench with Wooden Nesting Box / Techniques. A backhoe or ditchwitch is used to dig a ten to twelve foot long trench approximately three and a half feet deep. Then wooden nesting boxes are placed in the trench. The dimensions of the wooden nesting boxes are 2 1⁄2 feet by 11⁄2 feet. The boxes have a perforated drain pipe extending from the inside of the box on one side, at an angle to the surface of the ground, and extending about six to eight inches above the ground. Another length of perforated drainpipe can be similarly attached to another side of the nesting box and extended to the surface to serve as a back door. The trench is filled in, also covering the nesting boxes and drainpipe, with the dirt removed by the backhoe. The surface area is then re- vegetated.

A nest cap fashioned like a rabbit cage without a bottom is placed atop the perforated drainpipe that extends six to eight inches above ground. The nest cap is a 3 feet by 3 feet square that is 18 inches tall. There is a lightweight, hinged wooden door on the top that is used for putting the prairie dogs into the tube and for daily feeding. The nest cap is secured to the ground on each corner with 12-inch stakes.

The nest cap allows the prairie dogs to move from the nesting box below ground, to the surface above ground, and allows them to safely survey their surroundings while protecting them from predators.

On the first day of release, a good supply of slices of corn on the cob, lettuce, oats, carrots and sunflower mix should be left inside the nest cap. The corn, lettuce and carrots supply plenty of moisture. Food is supplied for the next three to five days.

The nest caps are removed at the end of five days, and the tube is cut down to just above ground level. Dirt is mounded around the tube so that just the very top is visible. Even after the nest caps are removed, the prairie dogs may be fed for a short while.

Prairie dogs may be labeled before being released into trenches, for monitoring purposes. Only one male prairie dog should be placed in a trench, unless there is certainty that they came from the same burrow at the capture site. It is best to release in the late afternoon as the prairie dogs are calmer and tend to stay in one place.

The release area should be re-vegetated where is has been disturbed, especially around the trenches. A backhoe with wheels instead of tracks is preferable, so as not to disturb the ground more than necessary.

A diagram of a wooden nesting box is included in Appendix 3.

Trench with Wooden Nesting Box / Strengths and Weaknesses. The greatest strength of using trenches with wooden boxes and nest caps is that the prairie dogs are provided with a nesting area that protects them from predators while they complete a burrow system and adjust to their new environment.

A weakness of this method is that trenching involves the cost of renting a backhoe or ditchwitch, and also the costs of the wooden boxes, nest caps and piping. Wooden nest boxes biodegrade much slower than cardboard nesting boxes. Additionally, the prairie dogs are not able to expand their immediate nesting area from a wooden box, and the boxes are much smaller than the cardboard ones. However, the wooden nesting box is far more durable. Prairie Dog Coalition in Boulder, Colorado prefers to use the wooden nesting boxes.

Trench with Cardboard Nesting Tube / Techniques. A tractor-style trencher backhoe is fitted with a twelve-inch bucket to dig a trench. The trench needs to be four feet deep, by one foot wide, by ten feet long and should be angled upward towards the surface. Quikreet tube, which is a cardboard commercial cement form, is then placed in the trench. The Quikreet tube should be eight-inches in diameter by four feet long by eight millimeters thick. Timothy grass hay and a shovel-full of dirt should then be placed in the bottom one third of the tube.

Square wooden blocks are used to cap both ends of the tubing. The blocks are made with hardwood that is 1⁄4 inch thick, and the dimensions of the blocks are nine inches by nine inches. Before attaching the wooden blocks to the tubing, four-inch holes should be cut into the center of the blocks. The wooden blocks are glued to the ends of the cardboard tubing. These wooden caps prevent dirt from seeping into the cardboard tubing. Then flexible plastic drain tubing, six feet long and four inches in diameter, is fitted into the holes in the wooden caps. The plastic drain tubing should extend into the cardboard tubing five or six inches. The plastic drain tubing extends above the ground six to eight inches, and a nest cap, as described above under wooden nesting boxes, is placed directly over the plastic drain tubing.

For a detailed description of the nesting boxes used by Prairie Dog Action in Colorado, please see Appendix 4.

Trench with Cardboard Nesting Tube / Strengths and Weaknesses. As with the wooden nesting boxes, this method provides protection from predators for relocated prairie dogs while they establish their burrow system in the new location. The cardboard nesting tubes have the advantage of allowing the prairie dogs to chew through and expand their nesting area from the one provided. All supplies used with this method are biodegradable. The nest caps and stakes are reusable and the cost is considerably less than with wooden nesting boxes. Also, the cardboard nesting tubes are somewhat larger than the wooden nesting boxes. A weakness is that they are not as durable as the wooden boxes, and in areas where there are badgers, they are known to dig into the cardboard nesting tubes.

Visual Barriers / Techniques. Visual barriers are materials placed around the outer perimeter of a release area to discourage prairie dogs from leaving the vicinity. There are several types, with a wide range in effectiveness and cost. All visual barriers need to be at least two feet in height.

One type of visual barrier is made from material fencing attached to wire and buried underground, extending above ground at least two feet. It is then secured to posts.

Concrete block walls are another type of visual barrier that are effective if made at least two feet high. Sometimes it is possible to obtain recycled concrete blocks for free.

Aluminum flashing is another fairly effective barrier and can be purchased at hardware stores. The flashing must be buried 18-21 inches underground with 25-30 inches kept above ground. Hardware cloth is a galvanized wire mesh that can be very effective, and is constructed like the aluminum flashing. The most effective visual barriers are native, drought resistant shrubs and grasses. Vegetative barriers are especially good as long-term barriers, but do take some time to become established.

Visual Barriers / Strengths and Weaknesses. Visual barriers can be an effective method to discourage relocated prairie dogs from expanding outside their release site. All barriers are not permanent and some are more effective than others. Unless native vegetation is utilized until maturity, the prairie dogs tend to find a way around the barrier. However, visual barriers can be helpful in confining prairie dogs until they become acclimated to a new environment.

Please see Appendix 5 for information on visual barriers that are suggested by the City of Boulder, Colorado in its “Urban and Suburban Black-Tailed Prairie Dog Colony Management Handbook.” Appendix 5 also includes information on visual barriers used by Prairie Dog Specialists.

CONCLUSION

The original directive for this report was to research auguring. Game and Fish was interested in using auguring so that release sites would not be restricted to abandoned prairie dog colonies. As the research proceeded it became clear that other site preparation methods could be as beneficial if not more beneficial than auguring. Auguring alone, the way it was utilized at the Raymond Wildlife Area, is not a technique that is currently being used by successful relocators in the southwest.

Most of the Colorado relocators, as well as the Hargrave Foundation in Texas and Prairie Ecosystems in New Mexico, all use sudsing for capture and trenching with some type of nesting box for release. Sudsing for capture provides the best opportunity to get the entire family group. This is most important for successful retention. Prairie Dog Action in Colorado reports a relocation in December of 2003 involving 150 prairie dogs with a retention rate of 90%. In addition, this group reports that every relocated female had babies the following spring. Prairie Dog Action boasts relocating 3,000 prairie dogs in the past 5 years using the sudsing method of capture with only 2 known fatalities. The two fatalities occurred when a burrow collapsed during sudsing due to recent heavy rainfall.

Trenching with some sort of nesting box provides adequate and immediate protection from predation so as to allow the prairie dogs to dig and finish their burrows. The nesting box provides an immediate nesting area, which adds to the retention rate. The animals feel more at home and inclined to stay and work on home improvements. The relocators who use a nesting box also use a nest cap, which sits above ground and is attached to the buried nesting box for feeding purposes. The prairie dogs can safely eat and eliminate for several days in the nesting cap until their new burrow is completed.

Relocation efforts in northern Arizona have been handicapped by the inadequate number of approved release sites. Utilizing trenching, some type of nesting boxes and nesting caps would increase the number of potential release sites, since an abandoned colony with existing burrows is not required. Not only would utilizing these methods create more release sites, but they would also increase both the capture rate and the survival rate of relocated prairie dogs.

During the course of this research, Ms. Deb Jones of Prairie Dog Action in Boulder, Colorado was contacted. Prairie Dog Action is privately owned and operated on a not-for-profit basis, and is licensed by the state of Colorado. Ms. Jones has been relocating black-tailed prairie dogs with Prairie Dog Action for the past five years. I explained the history and objectives of Habitat, as well as the techniques used by Habitat, and the current status of relocations in northern Arizona. Ms. Jones offered to come to Flagstaff to assist with our next relocation project, contingent upon acceptable scheduling. We would, of course, be expected to pay for her travel and lodging expenses.

Utilizing Ms. Jones’ experience to train our board members and supervise a relocation project this spring/summer would be advantageous to both Habitat and Game and Fish. Relocation work in northern Arizona seems to be stalled, both for lack of suitable release sites, and insufficient resources for Game and Fish. Presently, Habitat Harmony has funding from the grant we received from Flagstaff Community Foundation, which is earmarked for relocation work. By inviting Deb Jones to assist, and using the funds from the grant, we have a great opportunity. Habitat can test the techniques of sudsing, trenching and nesting boxes, under the supervision of a relocator experienced with these techniques. Both Habitat Harmony and Game and Fish would gain valuable experience and knowledge from the effort. This could be an opportunity to test the relocation techniques that have been researched in this report, and at the same time, help to preserve the local population of Gunnison’s prairie dogs.

REFERENCES

Boucher, Kathy. “Augering Prairie Dog Holes.” Prairie Dog Specialists. Accessed 23 January 2005. http://www.priairedogspecialists.org/Barrierspage.html

City of Boulder. 2002. Open Space and Mountain Parks Department. “Managing Prairie Dogs on Open Space and Mountain Parks.” Accessed 15 January 2005. http://www.ci.boulder.co.us/openspace/nature/pdogsmanagement.html

Chihuahuan Desert Lab Manual: Prairie Dogs – Project 3. Reintroduction and Monitoring of Prairie Dog Populations: A Study Proposal. Accessed 27 January 2005.

Dold, Catherine. “Making Room for Prairie Dogs” Home Portfolio. March 1998. Jones, Deb. Relocator and Vice President of Prairie Dog Action, Boulder, Colorado.

Telephone interview. 10 December 2005. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Jones, Deb. Telephone interview. 21 January 2005. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Lewis, J.C., Mcilvain, E.H., Mcvickers, R., and B. Peterson, 1979. Techniques used to establish and limit prairie dog towns. Proc. Okla. Acad. Sci. 59:24-30.

Petroglyphs. Marano, Nancy. Accessed 18 January 2005. “Prairie Dogs on the Move.” http://www.petroglyphsnm.org/covers/prairiedog.html

Petroglyphs. Regional and State Animal News and Views. “Animals Make Some Progress at State Capitol, Promise to be Back in 2005.” Spring 2004. http://www.petroglyphsnm.org/news/spr40news.html

Prairie Dogs Specialists – How Relocation Works. “How Relocation Works, Simply Put.” 12 January 2005. http://www.prairiedogspecialists.org/Relocation1page.html

Prairie Dog Specialists – Barriers. “Visible and Physical Barriers.” Accessed 18 January 2005. http://www.prairiedogspecialists.org/Barrierspage.html

Roe, Christopher and Roe, Kelly. “Recommended Black-Tailed Prairie Dog Relocation Guidelines.” 1 November 2002. Wildlife Property Management, LLC. www.YourWildlife.com

Sterling-Krank, Lindsey. Telephone interview. 10 December 2004. Prairie Dog Coalition. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Truett, Joe C. 16 July 1996. “Reintroduction of Black-tailed Prairie Dogs to the Ladder Ranch.” New Mexico.

A Message to Humans

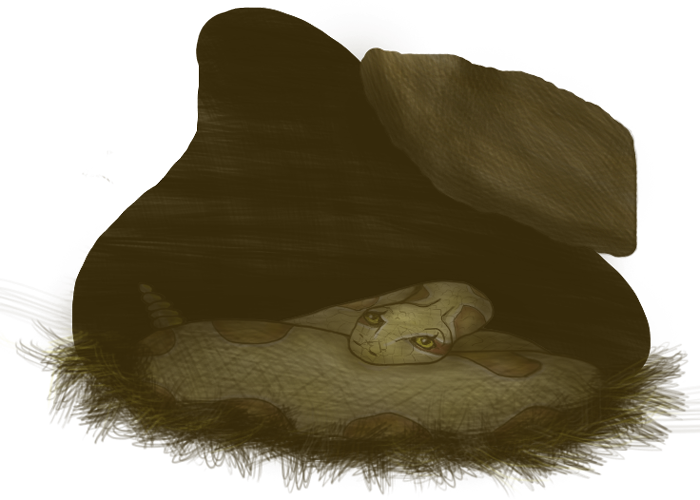

"I used to be a city fellow. I grew up with the city noises of cars and trains and machines and humans. My family lived close to downtown Flagstaff not far from the railroad tracks along Route 66. What a busy, frightening place it was."

Read My Letter to You