Latest News and Events

Doney Park-area prairie dogs get new home

By Emery Cowan

Originally published Aug. 19, 2018 in AZ Daily Sun | Link to original

Elise Wilson checks on a prairie dog trapped in a cage on a commercial plot of land recently in Timberline. Wilson and her husband Rob are building an indoor shooting range on the land and have been working to relocate the more than 100 prairie dogs that have been living in burrows there.

Jake Bacon/AZ Daily Sun

Working quietly, Elise Wilson squeezed the handle of the hose, sending a stream of soapy water gushing into the prairie dog hole beside her.

Across from her, Emily Renn knelt down, face inches from the dirt and hands hovering just inside the hole’s opening.

Slowly, a mass of bubbles began to rise up like white fluffy lava out of the hole. Both of the women watched closely, hoping that a prairie dog would come scampering out with the suds.

Over the past two weeks, the women have been on a mission to rescue the small burrowing rodents that live on Wilson’s property in Timberline, just west of U.S. Highway 89.

While the property is vacant now, Wilson and her husband Rob soon plan to build a 10,000 square-foot indoor shooting range on the land. But first they had to address the prairie dog holes that dot the property. GPS mapping found that there are 250 holes, which Renn estimated could mean up to 125 prairie dogs live in burrows beneath the surface.

Wilson, an animal lover to her core, couldn’t bear the thought of killing the little animals to pave over and build on the property, so she started searching for alternatives.

After some Googling, she found Renn’s organization, Habitat Harmony, which specializes in translocating prairie dogs from areas slated for development to more appropriate natural habitat.

Since Wilson made contact with the Flagstaff nonprofit, the prairie dog translocation project has grown to include participation and support from Coconino County, Arizona Game and Fish and Petrified Forest National Park, where the prairie dogs will be relocated.

It’s a major process that takes hours of work and several thousand dollars, but it’s the best shot at saving the animals.

Prairie dogs take a trip

After nearly two weeks, Renn and Wilson, with help from volunteers and Game and Fish employees, have captured and translocated 26 prairie dogs. They started off trying to capture the animals by spraying soapy water into their burrows, hoping to drive them to the surface. It’s a humane strategy because the animals can still breathe through the bubbles and the burrows dry out relatively quickly, Renn said. They also live-trapped the animals by tempting them out of their burrows and into small cages with sweetened grain.

After they’re captured, the prairie dogs will be taken to Petrified Forest National Park, which has about 90,000 acres of intact grasslands within its boundaries — one of the largest swaths of protected grasslands in the Southwest, said Andy Bridges, park biologist. Prairie dogs are native to the park and to northern Arizona, but since the 1990s populations have been declining, likely due to sylvatic plague, Bridges said.

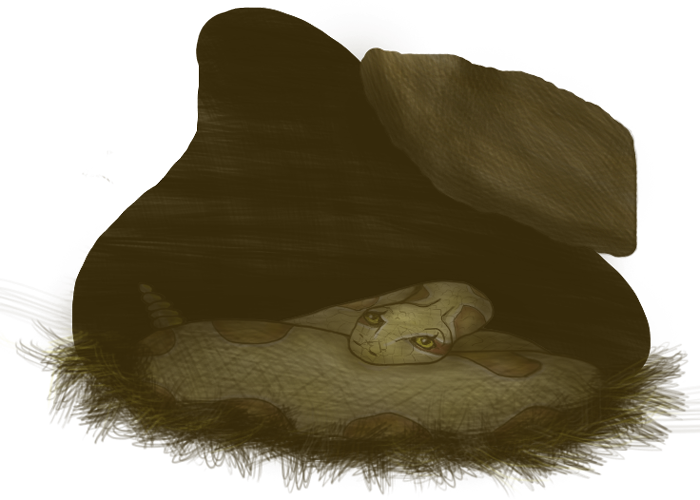

They’re a crucial part of the region’s grassland landscapes, though. The rodents' burrows provide habitat for other animals like snakes and burrowing owls, they help recycle nutrients as they dig up dirt and munch up foliage and their burrows help water penetrate into the soil.

In a place like Wilson’s property, though, where the prairie dogs have been squeezed into a smaller and smaller area by roads and development, they are no longer providing that benefit, said Hannah Griscom, urban wildlife planner with the Arizona Game & Fish Department.

Settling in

When the prairie dogs arrive at Petrified Forest, they are transferred to abandoned burrows that park staff have cleaned up a bit, Bridges said. The hope is to eventually establish enough prairie dog colonies that the park could reintroduce endangered black-footed ferrets there as well. That would take about 3,000 acres of colonies compared to the park’s current 275 acres of occupied burrows. The ferrets prey on prairie dogs, helping to keep the population in check, he said.

“We’re trying to maintain these lands in a state that's functioning naturally, but development and changes in climate are hard to keep up with if we have missing species,” Bridges said.

If construction does start on a prairie dog colony, the animals won’t tend to run out of their burrows and escape to a different location, Griscom said. Instead their tendency is to burrow deeper, which means they’ll be buried when the bulldozers start to do their work.

Renn estimated that the translocation project will cost about $7,000 in total and will continue through at least Monday. Wilson has raised nearly $1,000 of that through a Go Fund Me account for the project and the participating agencies have chipped in some money as well.

Somehow people have come to think it’s OK to plow over prairie dog habitat for development even though they’re just as important to keep around as any other species, Renn said.

“Think of other animals,” Renn said. “Birds would never be destroyed the way a prairie dog colony would be by developers.”