Latest News and Events

Prairie dogs getting new attention and respect

Originally printed in AZ Daily Sun on April 3, 2016 | Link to Original

by EMERY COWAN Sun Staff Reporter

A group of wildlife managers and interested residents crowded along a dirt road through Flying M Ranch on an unseasonably warm Friday last month. The group was there to learn about the prairie dogs that Flying M co-owner Kit Metzger says are starting to overrun her ranch, munching up grass and transforming about 7,000 acres of productive grazing land into an expanse of weeds and bare dirt.

“If they stay there long enough they kill all the grass off, then you get bare ground and all the issues that come with that,” Metzger said. “We can’t seem to change our management in any way to change their effects.”

Metzger emphasized that she knows prairie dogs are a native species and a key player in the larger community of plants and animals, but would like to find a better balance when it comes to the needs of the burrowing rodents and the needs of her cattle.

“We’ll live with some of them but we can’t live with that many of them,” she said.

Indeed, placing prairie dogs in the category of ranchland-destroying invaders would miss the larger narrative about these burrowing rodents’ role on the landscape. While considered a pesky nuisance by some, the species is a crucial component of the grassland ecosystem in the Four Corners region, including northern Arizona.

Local wildlife managers who specialize in prairie dogs say their work requires navigating between a range of perspectives on the rodents, from one that views them as prime competitors with ranching and agriculture to another devoted to helping the animals survive in any way possible.

And while prairie dogs may seem ubiquitous in places like Metzger’s ranch, over the past century, the species has lost 96 percent of its range, affecting not only grassland health but also the survival of the black-footed ferret, one of the most endangered mammals in the United States.

STRUGGLE FOR SURVIVAL

Prairie dog colonies once covered 100 million acres across 12 states in the Rockies and Great Plains regions. Now they are down to 3.7 million acres due to widespread poisoning and extermination campaigns in the early 20th century, the conversion of grasslands to cropland and housing developments and sylvatic plague, a disease introduced into Arizona in the 1930s.

Plague and habitat loss continue to make prairie dog population rebounds a struggle. There are also people, and even specifically organized coalitions, in the state that still believe it best to get rid of the animals, said Holly Hicks, the Arizona Game and Fish Department’s lead biologist for prairie dogs.

The rodents have gotten a bad rap in some people’s minds because they have significant and visible impacts on the landscape, said John Nystedt, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They also are seen as a competitor for both livestock and agriculture, which are the base of many people’s livelihoods, he said. Misinformation about things like the animals’ reproduction rates and their association with plague contribute to the negative perception as well, said Emily Renn, who works on prairie dog translocations with the nonprofit Habitat Harmony.

The rodents are key members of the grassland ecosystem, though.

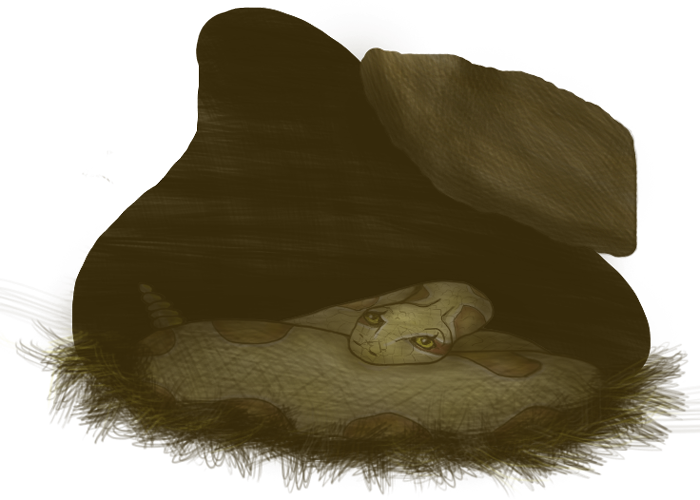

They are prey for hawks, coyotes, golden eagles and other animals while their burrows are used as shelter by a host of species, including snakes, rabbits and burrowing owls. Those tunnels also make it easier for rain or snowmelt to percolate through the ground to the water table, while their digging helps recycle nutrients into the soil, Hicks said. The prairie dogs’ nibbling stimulates new growth on plants, and studies have shown vegetation on burrows has a higher nutritional content than in other areas, Hicks said.

“Prairie dogs are a keystone species, so if you take prairie dogs out, a lot of things will change in their absence,” she said.

On Metzger’s ranch the effects appear to be different. The prairie dogs’ numbers have taken off since 2008, and everywhere the animals turn up seems to soon transform from high-producing grazing land into a denuded landscape, reducing the carrying capacity of the ranch’s winter range by 15 to 20 percent.

She has tried various strategies to reduce the animals’ numbers, from installing hawk poles to leaving piles of thinned juniper trees on the ground, but nothing has really worked.

A MORE POSITIVE PICTURE

Nystedt, who specializes in the native Gunnison’s prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets, was at the March visit to Flying M Ranch. He hasn’t seen the sort of issues Metzger is describing in other areas where there are large, dense colonies of prairie dogs, Nystedt said, leading him to think that the problem may be a mix of factors, some prairie-dog related and some not.

On Babbitt Ranches on the other hand, President and General Manager Bill Cordasco said he hasn’t noticed any impact positive or negative, of the voracious diggers on the productivity of the land.

Babbitt Ranches has actually welcomed relocated prairie dogs onto their property and has agreed to be a designated reintroduction location for black-footed ferrets, which requires maintaining a 3,000-acre corridor of prairie dog colonies.

Prairie dogs make up 90 percent of the endangered ferrets’ diet, and the reason for the animal’s near-extinction is “tied completely” to drastic reductions in prairie dog populations, Nystedt said.

Emily Renn, with Habitat Harmony, heads up local efforts to relocate prairie dogs in danger of losing their homes to development in and around Flagstaff. Relocations are effective but the process is complicated because prairie dogs ideally need to be relocated with animals in their same social group and can only be moved during a few months in the summer, Renn said.

Habitat Harmony also has a grant from the Arizona Game and Fish Department to explore nonlethal ways to manage prairie dog numbers. The department realizes that not everyone agrees with the ecosystem benefits of prairie dogs, but reducing the amount of poison applied on the landscape benefits all wildlife, Hicks said.

On a different track, researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center have spent more than a decade developing and testing an oral sylvatic plague vaccine for prairie dogs that is delivered via bait. The final round of field testing, which includes a site on Babbitt Ranches, is happening this summer so researchers should have results next year, USGS Research Scientist Tonie Rocke said.

Despite the importance of prairie dogs in the grassland ecosystem, Hicks acknowledged that at times there is competition between the rodents and ungulates, which is where the balance is needed.

“Compromise needs to come in on both ends,” she said.